GALLEY BEGGAR PRESS EXTRACTS

Wrestliana, by Toby Litt

MY FATHER LIKES TO TELL A JOKE, a story. Not on the page, in person. He does this better than I do. He’s friendlier and less self-conscious. He laughs, gives details when you need them, skips the boring bits, draws you in. One of the best true stories he knows is that of his great-great grandfather, William Litt. It has everything – a strong, handsome, tragic lead man. It involves crime, disloyalty, poetry and love. It’s a mystery story. It even has some epic fight scenes.

Since I was a boy, my father has told me this story – his version of it, anyway – perhaps a dozen times. He describes William’s triumphs, as champion Cumberland & Westmoreland wrestler and as writer of the first history of wrestling, and his failures in just about everything else. He speaks of William’s secret life as a smuggler, and his loss of a small fortune. He says that William was a sporting hero throughout the north of England, but that even today people are bitter about the debts he left behind. (When my father told the barman in the pub William used to run that he was his great-great grandson, he was told, ‘I wouldn’t mention that name in here.’) The story always ends the same way. William hops on a boat out of Whitehaven and flee to Canada – to ‘escape the local lord’.

This was the story my father told me when I told him and my mother that I wanted to be a writer. I was sixteen years old. We were sitting around the dining table – oval, pine.

I remember a pause.

I was relieved to have got it out, the announcement. I had been building up to telling them for years.

My father lounged in a Windsor chair that creaked at every shift. My mother sat upright on a chair like mine, wooden and antique but plain.

From Primary School on, I had been desperately trying to work out what I should do, what I should be. Dinosaur hunter. Vet. Soldier. Astronaut. The idea of having a vocation, something to give my life meaning, appealed to me long before I knew what a vocation was. I was drawn, I still don’t know why, to the idea of apprenticeship to a difficult craft.

‘Writing can be a very lonely business,’ said my father. He knew because his sister Shirley’s second husband had written and written, novel after novel, none of them published – and had left Shirley very much alone while doing so. ‘But if that’s what you want to do, that’s what you should do.’

I can’t remember what my mother said, unless it was that they both just wanted me to be happy.

We got up from the table.

‘Ee, son,’ my father finished by saying, in the Lancashire accent he puts on when he wants to disguise wisdom as wit, ‘p’raps it’s in your blood.’

He meant William.

About ten years later, when I had published a book, my father began to add a coda whenever he told me some newly discovered fact about William’s life: ‘It’s a great story – you should write it.’

But I had never taken this up – God, no!

Wasn’t I exactly the wrong person to tell William’s story? I was a puny Southern desk-worker who played video games – what did I have to do with this rugged Northern sportsman?

FIGURE 1. At the oval, pine dining table, signing copies of my first book for family and friends. Photo taken at my father’s insistence; smug expression, entirely down to me.

I knew nothing about Cumberland and Westmorland wrestling, the kind of wrestling William loved – at which he was good enough to win 200 belts. Although I’d grown up in Ampthill, a Georgian market town, in a Georgian house surrounded by Georgian furniture (bought and sold by my father, who dealt in antiques) most of what I knew about that period had come from Jane Austen.

The one physical connection I had with William was the family copy of his densely worded novel, Henry & Mary. This was kept on a bookshelf in the hall. I had been curious about it when I was a boy, because when you opened it, you didn’t just see print. It had some old-fashioned handwriting in the back. Someone had copied out a poem called ‘The Enthusiast’ and written under it ‘by William Litt “Author of Wrestliana”’. I had added some scribble, in pencil.

It was true that William and I had writing in common. But he was known as the author of the first ever history of wrestling – an early and important piece of sports journalism. My first book was called Adventures in Capitalism. In it, I wrote about made-up characters living in a very shallow, extremely technological now. I wrote about quick lives going violent and perverse and weird and sometimes haunted. That’s the kind of writer I was, not a historian or a historical novelist. I told the stories I wanted to tell, and they were about the world I lived in and the time I knew. My father was the antique dealer. The past belonged to him.

What I was really worried about, and had always been worried about, was that my father didn’t just own the past; he owned the present and future as well. He owned the whole world.

My writing had always been part of a struggle to prove my own existence, my own complete independence, from my family, but most of all from my father.

If I did owe anything to William Litt, if there really was something in the blood, then that blood had come to me through my father – and that was something I wasn’t ready to admit.

Yet.

Without me knowing it, my father had begun to do some of his own research. In 2005, he wrote to the Secretary of the Cumbria Family History Society. An article about William Litt had appeared in issue 109 of their magazine. He had heard it was very interesting. Could he have a copy?

Unfortunately, the Secretary replied, all copies were gone, even her own – but she could put my father in touch with the authors, Mr and Mrs William Hartley of Egremont, Cumbria.

My father wrote to the Hartleys, Bill and Margaret, who were delighted to hear from him. They knew exactly who Yours Sincerely David Litt was, because William Litt was also an ancestor of theirs. He was there in the family trees they had constructed, over the course of thirty years of research.

From local newspapers, they’d excavated William’s patriotic poems, his sports reports and his combative letters. In parish records, they’d discovered the fates of his children and grandchildren.

I got to read some of these in 2009. A visit had been arranged. My father and I took most of a long rainy day to drive up from Ampthill to Cumberland, to the Hartley’s comfortable bungalow.

They were very welcoming, quietly enthusiastic. Bill is a spruce, gentle voiced man. He had made much of the Georgian-style furniture in the house, chests of drawers and side tables. Margaret, equally soft-spoken, immediately made us feel comfortable – by serving us a proper roast dinner.

During the next couple of days, Bill took us to the sites of William Litt’s life. They were all very close together – his birthplace, the farm on which he grew up, the pub he mismanaged.

I was curious but not fascinated. Already, my father and the Hartleys had come to believe I was taking notes for a book I’d write, probably a historical novel with William as hero.

Finally, Bill took us to a cosy new-build cul-de-sac in Cleator Moor.

Our family place.

Not my place.

For a start, I didn’t speak the language.

I knew that in order to write The Life and Adventures of William Litt, a novel convincingly set in eighteenth and nineteenth century Cumberland, I would have to spend at least a year mastering the dialect.

The last evening of our visit, Bill took down his leather-bound dictionaries from the shelf beside the fireplace – they were full of wonderful words, words I would have loved to use, Oomer, Sneck-Posset, Yabble , but these dictionaries were not small.

And what would the story be? The paper trail – as the Hartleys shared it – was fascinating, but limiting. I didn’t want to make things up about William, and not enough was known to make a biography.

But these were excuses. The real reason was still my father.

As we drove back south the day after Bill took our photographs in Litt Place, I felt guilty. I didn’t think I would write this book, but I didn’t want to tell father. We stopped in a pub and had a pub lunch. I could have said then that it wasn’t going to happen, but I was scared to disappoint. Or make him angry.

‘Do you think you’ve got enough?’

‘Yes,’ I lied.

I wasn’t uninterested, I was just unable. So I went home and continued work on a novel. It had a subplot involving the poet John Keats, a contemporary of William, but was a long way away from Georgian Cumbria.

I didn’t tell my father, and Bill and Margaret, that I wasn’t writing about William, I just let other books, and life, get in the way.

I was father to two young sons, Henry and George. I had a job, teaching creative writing.

I think everyone understood.

And then, on February 13th 2012, my father’s birthday, my mother died.

Afterwards, for several weeks, I stayed with my father. I cooked his favourite meals – macaroni cheese, liver and bacon – foods my mother used to make. I watched Bargain Hunt and Pointless and the six and nine o’clock news with him. I did what I could, but it wasn’t enough.

My parents had been together for forty-six years. Theirs was the best marriage I’ve ever seen, though they were an odd couple, physically. My father was 6’5”; my mother, 5’1”.

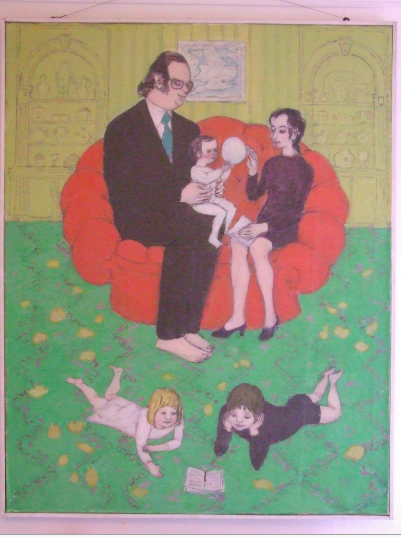

Figure 2. If the family portrait (by a German painter called Hannelore Köhler) is to be believed, I and my two sisters are the offspring of a giant and a witch.

Even when I was very young, I knew that although I’d definitely be bigger than my mum, I’d never be taller than my dad. The first memories I have of him aren’t so much of a human being as of a landscape. When I was a toddler, I used to climb him. He would be sitting on the sofa. It seemed to take me ages to get from his knees to his chest. He went on for miles.

I remember summer holidays in Cornwall – after swimming together in the sea, I would sit shivering between his legs, his vast towel wrapped around us. This was like being inside a sea cave. If I shouted, there came an imaginary echo. I felt very safe. I knew my father would protect me, would defend my two sisters.

One year, there was a huge guard dog that used to patrol the front garden of the bungalow next to ours. I remember it was a German Shepherd. When we children tried to sneak past, the hairy-muscly-teethy thing would rush at us, snarling, barking.

As we ate dinner, after a particularly terrifying walk back from the beach, I asked my father what he would do if the dog got out. He said, ‘I would put it over my knee and break it, like that.’ My mother tutted, but I believed him. All three of his children believed him. It took no imagination to see our father performing impossible feats of strength.

We knew that, at school, he’d been ‘shot-put champion of Shropshire’. In the sea at Cornwall, he would swim out so far that he was beyond our sight. He disposed of troublesome wasps by crushing them between forefinger and thumb.

As a boy, I was never afraid of getting lost in a big crowd, because I knew my father would be the tallest person there, and I’d always be able to find him.

Old age isn’t kind to men who have been big. My father now had type 2 Diabetes and continued to buy cakes and biscuits from the nice lady at the local farmer’s market. He walked with a stick. Getting out of a chair took a paragraph rather than a line.

Those weeks after my mother’s death were tough. My father missed her like a limb, and saw and heard her around the house. He suffered. He seemed completely defeated.

If I wanted to write the book he wanted to read, I had to write it soon.

But still.

It’s something lots of us have in common. We want to be different, to be original. We start out thinking that we come from nowhere and owe nothing to no-one. And that this is all good and necessary. Idiosyncrasy, self-reliance – yes.

Then, as years pass, we realize just how dependent on others we’ve always been, and how similar to them we now are. And rather than resenting this (although sometimes it’s still oppressive and daunting), we come to welcome it. We’re not alone.

Finally, we arrive at a point where we realize, we have to go back and take a good hard look at what really made us who we are. We have to acknowledge our debts. We have to measure ourselves against our forbears.

For me, with my mother’s death and with my father’s grief, this time had come. It had come from looking up and looking down – looking up at my father, who was becoming frail and forgetful and had never asked me to write anything except the story of William; looking down at my sons, who were desperately looking up at me for clues on how to grow up, how to be a man.

There are things I’d wanted to write about, ever since I began writing, but had never found a way to approach: being badly bullied at boarding school, and deciding the best I could do was never pass any violence on; going from being sporty (Public Schools Relays and First Fifteen) to being anti-sport; spending most of my life – like so many of us do – sitting looking at words on a computer screen.

In the Autumn of 2014, I sat down and read William’s book Wrestliana for the first time – and I suddenly saw a way in.

Through William.

Even during his lifetime, a friend referred to him as ‘a kind of anomaly in nature’ – an unprecedented combination of athletic superiority and literary talent.

William was like a combination of my father and I. Here was a man who was both a wrestler and a writer – who was both physical and intellectual.

This both is absolutely not me, and it’s not many other men – men who work at desks. It seems that this – balanced – is something we’re not able to be.

Perhaps because the two tribes, Jocks and Nerds, have become so far apart – their rituals and sacrifices; perhaps because we each of us have to hyperspecialize in order to become halfway good at any skill.

If you’re an athlete, you train so many hours of the day that you never have time to read a book; if you’re a writer or a programmer or an administrator, you spend so many years at the desk that your muscles go slack, your belly grows and your spine gets crocked. And if you’re well-balanced, you’re a well-balanced mediocrity.

But because William, somehow, was able – if only for a few years – to exist successfully in both worlds, physical and mental, he seemed to me an ideal figure: someone from whom I could learn things I needed to learn.

I decided to write a new book and to call it Wrestliana – to take William on, on his home ground. Because all of this being a man stuff was something I needed to wrestle with.

To be a better son and to be a better father. To be a better man.

Toby litt's memoir Wrestliana was published by Galley Beggar Press on 1 May 2018. the new statesman called it “disarmingly honest”. To order a copy, head here.